The Last One #1, July 1993, Vertigo/DC Comics

writer: J.M. DeMatteis

artist: Dan Sweetman

letterer: Todd Klein

assistant editor: Shelly Roeberg

editor: Karen Berger

What a difference a year makes. In the last 365 days, I've celebrated the births of children and the death of a friend, I've travelled countless hours and miles to spend memorable time with family, I've watched our country's search for its next President begin . . . and I've read just as many comic books. One for every day of the year -- actually, more, if you count my Free Comic Book Day marathon reviews, not to mention the books I already read on a frequent basis. More than once, particularly on those days when my responsibilities at work consumed my times and energy, I wondered why I so willing subjected myself to such a personal challenge. After all, I wasn't just reading comics; I was reading comics I'd never read before, one from a different series daily, which quickly became a test of the medium's availability, not just in the quest to find a worthy issue, but in the hope that it would keep my attention in the face of fatigue or apathy. Believe me, out of over 365 comic books, even a dedicated fan like me has to drag himself through more than one of them.

Yet therein lies why I wanted to endure this challenge in the first place. The comic book is an artistic endeavor that instantly warrants interaction from its audience, from the turning of the page to the visual incorporation of text and illustration. Further, as a monthly series, most comic book titles require a financial commitment from their readers if they want to read the whole story, or at least experience any given writer's or artist's talents again. As a collector of over fifteen years, I know that the medium boasts plenty of variety, and I know what I've liked, but how can I holistically support an art form if I haven't experienced everything it has to offer? Like television with its half-hour sitcoms and hour long dramas, or film with its buddy cop movie and documentaries, the comic book has a plethora of genres and subgenres to consider. Like many since-childhood fans, I'm primarily a superheroes kind of guy, but the likes of Batman and Spider-man became just a gateway for me to experience the virtual museum of graphic storytelling that is comics. Enter A Comic A Day, my personal dare to try something different, to subject myself to an entire medium's whims, regardless yet in consideration of its diverse contributors, cultural commentaries, and changing trends.

So, the question is, have I really learned anything?

Oh, yes. The contents of those first two paragraphs should offer some insight, but after 365 days of committed reading and analysis, I need to ween myself off of the habit. So, what better way to summarize my varied thoughts than by ending the summer with weekly series of essays about this past year's findings? See, despite today's issue's appropriate title, this is not the last A Comic A Day post. You get one more quarterly report, and then an eight-part year-end analysis. I'm professional like that.

Or crazy. Which brings us to The Last One #1.

When I discovered The Last One #1 in my local comic shop's quarter bin several months ago, I decided to horde it for today's review, despite my ignorance to the issue's contents. In fact, like many of the back issues at Comics, Toons, and Toys in Tustin, California, this issue was sealed shut, so I couldn't even give it the consideration of a flip test. Fortunately, the name J.M. DeMatteis has been good to me; though I appreciate him most for his co-writing contributions to the opus that is Justice League International, I remember him most for his stint on Amazing Spider-man. Following David Micheline, DeMatteis took Spidey down a dark post-parent-impostors/pre-Clone Saga path, pitting "the spider" against "the man" in an internal conflict that made my adolescent mind truly appreciate the dichotomy of the masked superhero. (The storyline starred Shriek and Carrion specifically and deserves its own trade. But I digress.) So, with just the encouragement of the writer's name, I considered this issue. It cost a quarter. To paraphrase Frank Miller, "I bought it anyway."

Boy, am I glad I did. More than once during this past year, while I sought some consistencies between my selected reads and, say, the holiday seasons, some connections were purely coincidental, surprising, and unavoidable -- synchronicities, I'd call them. Such is the case with The Last One, for while I wax on about this past year, this issue's protagonist suffers from the passage of time, though a bit longer than 365 days. Namely, this "last one" is actually one of the first ones, the last entity from a time before Creation, "When God lived so deep in every heart that He didn't even need a Name." When man was created and these free spirits chose oblivion over the prison of "coffin-flesh," one entity stuck around, introduced in this miniseries as a hermaphroditic den-keeper for the city's lost souls. Through prophetic figurines (that look like Monopoly pieces), this being drives these orphans of fate to embrace their potential and forsaken destinies, and while this eternal is one part inspiration, he is also one part definitively outsider, as s/he explains, "The longer I live, the less I understand. Communication . . . sometimes the simplest communication . . . just gets harder and harder. We're all revolving in our little universes . . . so cut off . . ."

Enter the iPhone. Timely, indeed.

DeMatteis' script captures the ethereal in a very terrestrial way, transfiguring the existence of pre-creation entities via sympathetic text, and while his narrative borders on lofty, it steers clear of any old English or King James-like vernacular, as one might expect from material about the divine. No, DeMatteis keeps us as grounded as his protagonist, and the paintings of Sweetman elevates this dichotomy expertly. Fans of Mack and McKean would thoroughly enjoy his illustrations, because from page one they offer stimulating tangible imagery while clearly supporting the writer's spiritual themes and intentions. When DeMatteis described that his lead had features that both appeared masculine and feminine, all the while lumbering in an "elephantine body," I wondered if Sweetman would be able to put off such a description, but he rises to the challenge and in fact takes the task to a whole new level. Not to make light of his effort, our hero is one part Mrs. Doubtfire, one part Morpheus from The Matrix: a sage-like caretaker with the weight of the world on his/her shoulders and a simmering mystery brewing underneath.

The Last One was the best comic book with which I could've concluded this challenge. While my initial intentions were to close on an iconic character, like Superman with whom I began, this hero's consideration of the context of time puts the past year in perspective. In the past 365 days, I've seen over half a dozen comics to film projects. The coffee shop where I wrote that first review of Superman #300 has since closed down. But compare that to eternity? A Comic A Day doesn't hold a candle . . . and considering that my quest for these comics has revealed that the medium has a seemingly endless amount of material from which to learn, this project is still but a microcosm of one fan's lifetime experience. I could continue for years, reading one issue from a different series every day, and maintain the integrity of this process indefinitely. The comic book as an issue may be a standard twenty-two page sequentially graphic story, but as an art it's a century-old time capsule of cultural reflection, fantastic escape, and diverse talent. This issue may be the final review in a sequence of 365 consecutive reflections, but for me as a collector, fan, and student of the comic book medium, it is by no means the last one.

Saturday, June 30, 2007

Friday, June 29, 2007

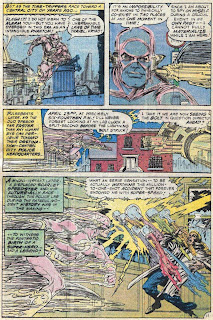

The Outsiders #28

The Outsiders #28, February 1988, DC Comics

writer: Mike W. Barr

penciller: Erik Larsen

inker: Mark Farmer

letterer: Albert Deguzman

colorist: Adrienne Roy

editor: Andrew Helfer

For my penultimate review, since I’ve read so many number one issues this year, I thought I should experience the other side of a series by analyzing a final issue, and fortunately I found one to my liking and have been reserving it for this post for eleven months. As I’ve explained a few times before, though I grew up on superhero cartoons and action figures, I didn’t become an avid reader until my father recovered a box of nearly discarded comic books and left them at the foot of my bed. That fateful morning, I read Amazing Spider-man #347, and while I loved the story, Erik Larsen’s pencils grabbed me in a way I hadn’t been before. His work seemed so stylized and expressive to me, unlike the rigid promotional pieces that adorned the Super Powers packaging or minicomics, that I had to have more – thus, a collector was born! So, for this final issue of The Outsiders to sport some more of his early work, I feel like my yearlong effort has come full circle.

Such is the plight for the Outsiders’ Looker in this issue. In a retelling of her origin, Looker explains that her average appearance was transformed when the underground Abyssian race claimed her as an heir to their throne, and though her husband rejected her new beauty, she embraced her heroic responsibilities, eventually joined the Outsiders that rescued her from underworld war. Now, beckoned by the Abyssians again, who have in turn been besieged by a splinter group of Manhunters, Looker is captured by and must confront the Abyssians’ self-proclaimed (and therefore evil) princess, who has mimicked Looker’s powers and, in their climatic battle, takes them away, returning the heroine into her former, plain Jane self. The rest of the Outsiders ably assist her, and even when one of them falls, the ragtag heroes defeat the Manhunters dutifully. Surely theirs is a Pyrrhic victory, proving that no good deed goes unpunished, yet touched with the promise that the Outsiders will rise again. You really can’t keep a good superhero team down.

If I had been a fan of the Outsiders when this issue was originally released, I might have been peeved that their final adventure was incorporated into a multi-title crossover – in this case, the Manhunters-centric Millennium, but writer and co-creator Mike W. Barr manages to let his team shine despite the mire of other titles’ happenings. In fact, by bringing the Manhunters to the Abyssians, he makes the poignant point that no corner of the DC Universe is safe while highlighting the inner conflicts of one of his protagonists, which is a fair and balanced approach to the crossover epic in general. By confronting the Manhunters almost effortlessly, while at the same time these aliens are giving the Justice League a run for their money, Barr takes this story to an predominantly introspective arena – a place where I’d prefer to see a favorite series end, anyway. Yeah, I’d be peeved, but only until I finished reading the issue.

And what can I say about Erik Larsen’s art? You know I like, though this issue obviously isn’t his best work. These early Larsen samples are really just teasers of what his style would become; under the intricate inkery of Mark Farmer, Larsen betrays his love of Kirby and keeps a simple line to many of his characters’ expressions. When he’s illustrating his own characters, Larsen is much more detail oriented, perhaps because the only true critic of this intimate subject material is himself, sans the baggage of previous creators’ interpretations. While this effort is evident in the current Savage Dragon series, I was recently fortunate enough to discover the Dragon’s very first, pre-Image appearance in the Gary Carlson-driven fanzine Megaton. In the second issue (I found #2, #4, and #5), the Dragon appears briefly as a bounty hunter out for the alien Vanguard, a foreshadowing of their first meeting in Larsen’s Image/Highbrow Universe. Of course, I couldn’t find the follow-up issue featuring their slugfest, but even this quick cameo exudes Larsen’s care for his own creation. The Outsiders #28 is still an eye-catching action packed issue, with expert page layouts and fluid fight sequences, but as in most cases, context is the key to a greater understanding of this work. Art is funny that way.

First issues operate under the presumption that their respective stories will successfully introduce their story in such a way that the reader is instantly invested in their characters and implications. Who would've thought that a last issue could have a similar impression even (or especially) when it's inadvertently and ironically someone's initial experience with that title? Barr and Larsen assert a familiarity with the Outsiders, with nudges toward their long time fans, while remembering that every comic could end up being someone's first. Indeed, everybody that first comic, the one that made them decide, "Yes, I'm going to wipe out half of my savings this weekend to collect every appearance of this character!" or, "No, I don't like it, and further I'm going to make an effort to beat up everybody that does." Of course, I fell into the former category . . . and after a year of complete immersion, I'm more steadfast than ever.

I'll see you at the finish.

writer: Mike W. Barr

penciller: Erik Larsen

inker: Mark Farmer

letterer: Albert Deguzman

colorist: Adrienne Roy

editor: Andrew Helfer

For my penultimate review, since I’ve read so many number one issues this year, I thought I should experience the other side of a series by analyzing a final issue, and fortunately I found one to my liking and have been reserving it for this post for eleven months. As I’ve explained a few times before, though I grew up on superhero cartoons and action figures, I didn’t become an avid reader until my father recovered a box of nearly discarded comic books and left them at the foot of my bed. That fateful morning, I read Amazing Spider-man #347, and while I loved the story, Erik Larsen’s pencils grabbed me in a way I hadn’t been before. His work seemed so stylized and expressive to me, unlike the rigid promotional pieces that adorned the Super Powers packaging or minicomics, that I had to have more – thus, a collector was born! So, for this final issue of The Outsiders to sport some more of his early work, I feel like my yearlong effort has come full circle.

Such is the plight for the Outsiders’ Looker in this issue. In a retelling of her origin, Looker explains that her average appearance was transformed when the underground Abyssian race claimed her as an heir to their throne, and though her husband rejected her new beauty, she embraced her heroic responsibilities, eventually joined the Outsiders that rescued her from underworld war. Now, beckoned by the Abyssians again, who have in turn been besieged by a splinter group of Manhunters, Looker is captured by and must confront the Abyssians’ self-proclaimed (and therefore evil) princess, who has mimicked Looker’s powers and, in their climatic battle, takes them away, returning the heroine into her former, plain Jane self. The rest of the Outsiders ably assist her, and even when one of them falls, the ragtag heroes defeat the Manhunters dutifully. Surely theirs is a Pyrrhic victory, proving that no good deed goes unpunished, yet touched with the promise that the Outsiders will rise again. You really can’t keep a good superhero team down.

If I had been a fan of the Outsiders when this issue was originally released, I might have been peeved that their final adventure was incorporated into a multi-title crossover – in this case, the Manhunters-centric Millennium, but writer and co-creator Mike W. Barr manages to let his team shine despite the mire of other titles’ happenings. In fact, by bringing the Manhunters to the Abyssians, he makes the poignant point that no corner of the DC Universe is safe while highlighting the inner conflicts of one of his protagonists, which is a fair and balanced approach to the crossover epic in general. By confronting the Manhunters almost effortlessly, while at the same time these aliens are giving the Justice League a run for their money, Barr takes this story to an predominantly introspective arena – a place where I’d prefer to see a favorite series end, anyway. Yeah, I’d be peeved, but only until I finished reading the issue.

And what can I say about Erik Larsen’s art? You know I like, though this issue obviously isn’t his best work. These early Larsen samples are really just teasers of what his style would become; under the intricate inkery of Mark Farmer, Larsen betrays his love of Kirby and keeps a simple line to many of his characters’ expressions. When he’s illustrating his own characters, Larsen is much more detail oriented, perhaps because the only true critic of this intimate subject material is himself, sans the baggage of previous creators’ interpretations. While this effort is evident in the current Savage Dragon series, I was recently fortunate enough to discover the Dragon’s very first, pre-Image appearance in the Gary Carlson-driven fanzine Megaton. In the second issue (I found #2, #4, and #5), the Dragon appears briefly as a bounty hunter out for the alien Vanguard, a foreshadowing of their first meeting in Larsen’s Image/Highbrow Universe. Of course, I couldn’t find the follow-up issue featuring their slugfest, but even this quick cameo exudes Larsen’s care for his own creation. The Outsiders #28 is still an eye-catching action packed issue, with expert page layouts and fluid fight sequences, but as in most cases, context is the key to a greater understanding of this work. Art is funny that way.

First issues operate under the presumption that their respective stories will successfully introduce their story in such a way that the reader is instantly invested in their characters and implications. Who would've thought that a last issue could have a similar impression even (or especially) when it's inadvertently and ironically someone's initial experience with that title? Barr and Larsen assert a familiarity with the Outsiders, with nudges toward their long time fans, while remembering that every comic could end up being someone's first. Indeed, everybody that first comic, the one that made them decide, "Yes, I'm going to wipe out half of my savings this weekend to collect every appearance of this character!" or, "No, I don't like it, and further I'm going to make an effort to beat up everybody that does." Of course, I fell into the former category . . . and after a year of complete immersion, I'm more steadfast than ever.

I'll see you at the finish.

Thursday, June 28, 2007

Strange Galaxy #8

Strange Galaxy #8, February 1971, Eerie Publications

The A Comic A Day project has been an incredibly challenging undertaking, not so much because I’ve had to read and review a comic book every day for a year despite my sometimes busy schedule. I initiated this blog under the presumption that I was reading a comic book every day anyway, so why not just read one I’d never had before and chronicle my thoughts about it? Of course, venturing out of my own collection in search of different and eclectic books was the scary part, assuming I’d inevitably encounter issues and even genres I just wouldn’t like. The “comic book magazine” was one of those gambles. If my experience could be likened to an astronaut’s launch into the unknown, these magazines were strange galaxies, indeed.

Yet I enjoyed each and every one of them. From the Epic Illustrated I reviewed on the second day of this project to the Heavy Metal issue I read around Christmastime, each book has offered a variety of storytelling and artistic techniques I never would’ve experienced before. These anthologies are proof that the length of a comics story doesn’t matter in the face of a dynamic concept and stylized illustration, and further that these shorts can be combined to create a sampling of what any given genre or era has to offer. Today’s issue, Strange Galaxy #8, features seven stories about space and death, both respectively dark abysses that pose introspective and exploratory inquiries about the unknown. Just as these anthologies show us more about the comics medium, these questions reveal more about the nature of man. Strange Galaxies therefore is evidence of both phenomena!

The best way to review this magazine is by breaking it down by story, with a brief synopsis and review, as follows:

The Unknown: When a band of astronauts venture into space, they’re overwhelmed by the experience and driven to madness perceiving the stars and planets in the same visual dimension as from Earth; Mars looks like a tennis ball, and Jupiter, a balloon! The concept is a laughable one but presented with a psychological, thrilling succinctness – a perfect first story for a book with a title like Strange Galaxy. Also, the art in this story was brilliant, and it reminded me of today’s Eric Powell. Dark and dramatic, this tale might’ve actually dissuaded an entire generation from the youthful hopes of becoming an astronaut!

Planet of Horror: Another tale of interstellar exploration, this yarn depicts a band of “glory hunters” in pursuit of a long lost scientist, and when they find him leading a utopian society, he brainwashes them into remembering a horrific experience and sends them home in the hopes not to be disturbed again. Unfortunately, their boss hid cameras in their equipment and discovers the truth, only to fall by the scientist’s laser gun. This story could be a contemporary analogy for international invasion, simply elevated to a cosmic scale, so I appreciated its suspense and vitality.

Space Monsters: Has a story ever had a clearer title? Yes, heroic astronaut Don Benton and a hapless tagalong reporter face an army of space monsters under the mind control of a large radiated brain, and when Benton fashions a lead helmet for the brain’s capturers, they defeat the gray matter and escape. This adventure starts strong but jumps the shark in its brief eleven pages, still providing a rollicking good time for readers. Again, the art was definitive of this genre and era, beautiful to behold though a little stiff for its correspondingly melodramatic narrative. The panel of Captain Benton fighting like a “trapped canal cat” leaves something to be desired . . .

But not as much as The Moon is Red, a parable about a lunar colony struggling to achieve political vitality. Clearly the weakest in production, this story has the strongest potential, but something holds it back from achieving the reverence of the other three space adventures. Perhaps I was merely lost in its lofty study of an early civilization, in this case tainted by alien despots, and coupled with the torrent love affair of its future king and queen. Too many threads for an already high concept plot, is all. Still, the weakest of this anthology is still compelling by today’s standards, a fun, pulpy space epic.

The last three tales in this magazine take a macabre twist starting with Voodoo Doll, in which a professor of the supernatural acquires some voodoo clay from a forbidden grave in Haiti, and, despite his self-imposed logic, begins using it toward his own ends, killing “enemies” in his realm of academia. Of course, this strange tale takes a Monkey’s Paw turn when the prof’s admiring son makes a doll of his father with the clay, and though the professor locks it in a safe to assure his safety, he ends up suffocating as if he were imprisoned himself. This is a plot truly deserving of a Twilight Zone episode.

Flaming Ghost and Terror of the Dead are similar in that they embrace the supernatural with little explanation behind their climatic, frightening anomalies. For example, in Flaming Ghost, a jealous mortician burns his potentially cheating (but not really) wife alive, and when he taunts her ashes, she arises from the urn in a skeletal form to throw hubby in the flames for a taste of his own medicine. What befuddles me most is how such a human-sized skeleton could squeeze out of an urn, but if this story teaches us anything, it’s not to underestimate the dead.

Likewise, in Terror of the Dead, a gravedigger gruesomely collects the dead, vilest parts of his tormentors, like the tongue of the town gossip or the torso of the high school football star. Unfortunately, when the digger’s unrequited love is mistaken for dead, put in his care only to arise and reject, then murdered by his hand only to tell her fellow corpses about the creep’s injustices against them, these body parts form a strange Frankenstein-like uber-bully and effortlessly kill him. I liked these tales, but since Voodoo Doll had a mystical methodology behind it, I had a hard time embracing this “strangeness for strangeness’ sake” style. Then again, this mag isn’t called Strange Galaxy for nothing.

Although the A Comic A Day challenge will be complete by the time I venture to the San Diego Comic Con this year, I’ve resolved to seek out more anthologies like this there. I may not be reviewing them for public consumption, but the point of this project was to expose myself to new things. What would be the point if I didn’t stick to these new interests? What would be the point of venturing into a strange galaxy if one didn’t intend to stay there awhile, no matter how many monsters or ghosts lurked around the corner?

The A Comic A Day project has been an incredibly challenging undertaking, not so much because I’ve had to read and review a comic book every day for a year despite my sometimes busy schedule. I initiated this blog under the presumption that I was reading a comic book every day anyway, so why not just read one I’d never had before and chronicle my thoughts about it? Of course, venturing out of my own collection in search of different and eclectic books was the scary part, assuming I’d inevitably encounter issues and even genres I just wouldn’t like. The “comic book magazine” was one of those gambles. If my experience could be likened to an astronaut’s launch into the unknown, these magazines were strange galaxies, indeed.

Yet I enjoyed each and every one of them. From the Epic Illustrated I reviewed on the second day of this project to the Heavy Metal issue I read around Christmastime, each book has offered a variety of storytelling and artistic techniques I never would’ve experienced before. These anthologies are proof that the length of a comics story doesn’t matter in the face of a dynamic concept and stylized illustration, and further that these shorts can be combined to create a sampling of what any given genre or era has to offer. Today’s issue, Strange Galaxy #8, features seven stories about space and death, both respectively dark abysses that pose introspective and exploratory inquiries about the unknown. Just as these anthologies show us more about the comics medium, these questions reveal more about the nature of man. Strange Galaxies therefore is evidence of both phenomena!

The best way to review this magazine is by breaking it down by story, with a brief synopsis and review, as follows:

The Unknown: When a band of astronauts venture into space, they’re overwhelmed by the experience and driven to madness perceiving the stars and planets in the same visual dimension as from Earth; Mars looks like a tennis ball, and Jupiter, a balloon! The concept is a laughable one but presented with a psychological, thrilling succinctness – a perfect first story for a book with a title like Strange Galaxy. Also, the art in this story was brilliant, and it reminded me of today’s Eric Powell. Dark and dramatic, this tale might’ve actually dissuaded an entire generation from the youthful hopes of becoming an astronaut!

Planet of Horror: Another tale of interstellar exploration, this yarn depicts a band of “glory hunters” in pursuit of a long lost scientist, and when they find him leading a utopian society, he brainwashes them into remembering a horrific experience and sends them home in the hopes not to be disturbed again. Unfortunately, their boss hid cameras in their equipment and discovers the truth, only to fall by the scientist’s laser gun. This story could be a contemporary analogy for international invasion, simply elevated to a cosmic scale, so I appreciated its suspense and vitality.

Space Monsters: Has a story ever had a clearer title? Yes, heroic astronaut Don Benton and a hapless tagalong reporter face an army of space monsters under the mind control of a large radiated brain, and when Benton fashions a lead helmet for the brain’s capturers, they defeat the gray matter and escape. This adventure starts strong but jumps the shark in its brief eleven pages, still providing a rollicking good time for readers. Again, the art was definitive of this genre and era, beautiful to behold though a little stiff for its correspondingly melodramatic narrative. The panel of Captain Benton fighting like a “trapped canal cat” leaves something to be desired . . .

But not as much as The Moon is Red, a parable about a lunar colony struggling to achieve political vitality. Clearly the weakest in production, this story has the strongest potential, but something holds it back from achieving the reverence of the other three space adventures. Perhaps I was merely lost in its lofty study of an early civilization, in this case tainted by alien despots, and coupled with the torrent love affair of its future king and queen. Too many threads for an already high concept plot, is all. Still, the weakest of this anthology is still compelling by today’s standards, a fun, pulpy space epic.

The last three tales in this magazine take a macabre twist starting with Voodoo Doll, in which a professor of the supernatural acquires some voodoo clay from a forbidden grave in Haiti, and, despite his self-imposed logic, begins using it toward his own ends, killing “enemies” in his realm of academia. Of course, this strange tale takes a Monkey’s Paw turn when the prof’s admiring son makes a doll of his father with the clay, and though the professor locks it in a safe to assure his safety, he ends up suffocating as if he were imprisoned himself. This is a plot truly deserving of a Twilight Zone episode.

Flaming Ghost and Terror of the Dead are similar in that they embrace the supernatural with little explanation behind their climatic, frightening anomalies. For example, in Flaming Ghost, a jealous mortician burns his potentially cheating (but not really) wife alive, and when he taunts her ashes, she arises from the urn in a skeletal form to throw hubby in the flames for a taste of his own medicine. What befuddles me most is how such a human-sized skeleton could squeeze out of an urn, but if this story teaches us anything, it’s not to underestimate the dead.

Likewise, in Terror of the Dead, a gravedigger gruesomely collects the dead, vilest parts of his tormentors, like the tongue of the town gossip or the torso of the high school football star. Unfortunately, when the digger’s unrequited love is mistaken for dead, put in his care only to arise and reject, then murdered by his hand only to tell her fellow corpses about the creep’s injustices against them, these body parts form a strange Frankenstein-like uber-bully and effortlessly kill him. I liked these tales, but since Voodoo Doll had a mystical methodology behind it, I had a hard time embracing this “strangeness for strangeness’ sake” style. Then again, this mag isn’t called Strange Galaxy for nothing.

Although the A Comic A Day challenge will be complete by the time I venture to the San Diego Comic Con this year, I’ve resolved to seek out more anthologies like this there. I may not be reviewing them for public consumption, but the point of this project was to expose myself to new things. What would be the point if I didn’t stick to these new interests? What would be the point of venturing into a strange galaxy if one didn’t intend to stay there awhile, no matter how many monsters or ghosts lurked around the corner?

Wednesday, June 27, 2007

The Flash #309

The Flash #309, May 1982, DC Comics

writer: Cary Bates

penciller: Carmine Infantino

inker: Dennis Jensen

colorist: Gene D'Angelo

letterer: Milt Snapinn

editor: Mike W. Barr

While Marvel's superheroes have attained iconic status in worldwide pop culture and continue to star in their own feature length films, DC's roll call are the founding fathers of the genre, a feat that needs no supplemental media to prove its significance. However, while fans have criticized DC's (and, really, Warner Brothers') inability to produce comics-to-film projects as quickly as Marvel (sixteen films from the House of Ideas pales to DC's three in the last decade . . . and I'm including Catwoman), the Distinguished Competition has conversely cornered the television market, producing the undeniably successful Smallville and a multitude of animated series and straight-to-DVD animated specials. In fact, considering these shows, the WB may be responsible for more total hours of filmed entertainment than Marvel since the comparison became viable in the late '90s (inspired not by Spider-man, but Blade). So, all that is to say, I'm standing by the DC stable. I may not agree with the current direction of the DC Universe, but I have plenty of nostalgic canon at my disposal.

Which is why I was so excited to read Flash #309, which is actually a timely review considering last week's tumultuous events in the Scarlet Speedster's life. Since I'm not collecting The Flash and have been blissfully ignorant of most of the 52-related phenomenon, I'll confess I'm not completely privy to that latest issue's details, but a flip of the book gave me a fair impression of its implications. Again, I may not agree with this direction, but it proves the point the issue of The Flash that I read today solidified: of all of DC's canon, the Flash is the most influential to the superhero genre. Now, I know what my fellow fanboys might be thinking -- when compared to Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, and even Captain Marvel, why would the Flash hold the distinction of "most influential?" I mean, he really just runs, right? Yes, he does, which is my point exactly. The Flash has always been a progressive, as a concept and as a character.

First of all, in his original Golden Age incarnation, the Flash was a gamble, because his sole power was but one of Superman's -- a concept not as well defined in the hit-or-miss superhero cavalcade of the '40s, but true nevertheless. Further, the Flash's reboot, the first official revamp in superhero fiction, initiated the Silver Age and redefined the way comics told stories. Despite their many interpretations through the '80s, superheroes remained colorful campy adventurers until DC's first Crisis, you know, the one on Infinite Earths, in which the company actually sacrificed one of their own to again usher a new generation of characters into their ranks. Indeed, before Robin and Superman died or Batman suffered a broken back, Barry Allen willingly bit the big one, becoming the first widely known superhero to die. None of the other similar gimmicks inflicted to DC's other heroes have lasted as long. The Flash has always been racing ahead of his time.

Which brings me to The Flash #309, a refreshingly villain-free story that epitomizes why the Flash is the most innovative superhero of all. In this issue, a refugee from a warring future travels back in time in search of a legendary Justice Leaguer to help him save his people, and he finds and mistakenly attacks Barry to harvest the Speedster's power. Of course, the Flash eludes his attempts and discovers his motives, which originally included commandeering Green Lantern's ring. The weird little creature's (assumed to be the next evolutionary stage of man) search wasn't for the hero himself but the weapon, and while he surmises a way to take the Flash's speed, Barry comes up with an alternative plan: traveling back further in time to the point of his super-heroic origin, the Flash gives the alien the chemical-drenched clothes he was wearing when struck by that fateful bolt of lightning, effectively creating a Flash for the future! Unfortunately, this Flash doesn't last long, defeating the monster in the future by grabbing it and accelerating his molecules to the point of mutual spontaneous combustion. See, even in the 98th century, the Flash is hailed as a selfish hero . . . which is what I've been trying to get at in the first place.

As both a character in the continuity of his comic book universe and as an icon of the industry, the Flash has always given of himself to assure victory and success. In the case of his Silver Age transition, the Speedster actually abandoned his original secret identity, becoming the re-imagined Barry Allen, and though Jay Garrick eventually returned as an active member of the Justice Society, Barry has since held the longest stint as the Fastest Man Alive (with Wally West and Impulse carrying the torch afterward). Further, in order to assure that such an epic crossover like Crisis on Infinite Earths boasted relevance and viability, Flash was the hero on the chopping block, willingly, even. Heck, the Flash live action series, though short-lived, set the stage for DC's contemporary tradition of bringing its heroes to the small screen. Superman may have been the first superhero, but the Flash has held the title of being the first to make some ultimate sacrifices.

I don't have to talk about how incredible Carmine Infantino's art is in this issue, do I? Definitive for the character and the era. Perfect superhero dynamics, perhaps DC's answer to the Romitas at Marvel. 'Nuff said.

Perhaps DC is taking the slow and steady method to producing its live action feature films. Yet, when it comes to producing heroes, those who put others before themselves . . . they've always been able to do that in a flash.

writer: Cary Bates

penciller: Carmine Infantino

inker: Dennis Jensen

colorist: Gene D'Angelo

letterer: Milt Snapinn

editor: Mike W. Barr

While Marvel's superheroes have attained iconic status in worldwide pop culture and continue to star in their own feature length films, DC's roll call are the founding fathers of the genre, a feat that needs no supplemental media to prove its significance. However, while fans have criticized DC's (and, really, Warner Brothers') inability to produce comics-to-film projects as quickly as Marvel (sixteen films from the House of Ideas pales to DC's three in the last decade . . . and I'm including Catwoman), the Distinguished Competition has conversely cornered the television market, producing the undeniably successful Smallville and a multitude of animated series and straight-to-DVD animated specials. In fact, considering these shows, the WB may be responsible for more total hours of filmed entertainment than Marvel since the comparison became viable in the late '90s (inspired not by Spider-man, but Blade). So, all that is to say, I'm standing by the DC stable. I may not agree with the current direction of the DC Universe, but I have plenty of nostalgic canon at my disposal.

Which is why I was so excited to read Flash #309, which is actually a timely review considering last week's tumultuous events in the Scarlet Speedster's life. Since I'm not collecting The Flash and have been blissfully ignorant of most of the 52-related phenomenon, I'll confess I'm not completely privy to that latest issue's details, but a flip of the book gave me a fair impression of its implications. Again, I may not agree with this direction, but it proves the point the issue of The Flash that I read today solidified: of all of DC's canon, the Flash is the most influential to the superhero genre. Now, I know what my fellow fanboys might be thinking -- when compared to Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, and even Captain Marvel, why would the Flash hold the distinction of "most influential?" I mean, he really just runs, right? Yes, he does, which is my point exactly. The Flash has always been a progressive, as a concept and as a character.

First of all, in his original Golden Age incarnation, the Flash was a gamble, because his sole power was but one of Superman's -- a concept not as well defined in the hit-or-miss superhero cavalcade of the '40s, but true nevertheless. Further, the Flash's reboot, the first official revamp in superhero fiction, initiated the Silver Age and redefined the way comics told stories. Despite their many interpretations through the '80s, superheroes remained colorful campy adventurers until DC's first Crisis, you know, the one on Infinite Earths, in which the company actually sacrificed one of their own to again usher a new generation of characters into their ranks. Indeed, before Robin and Superman died or Batman suffered a broken back, Barry Allen willingly bit the big one, becoming the first widely known superhero to die. None of the other similar gimmicks inflicted to DC's other heroes have lasted as long. The Flash has always been racing ahead of his time.

Which brings me to The Flash #309, a refreshingly villain-free story that epitomizes why the Flash is the most innovative superhero of all. In this issue, a refugee from a warring future travels back in time in search of a legendary Justice Leaguer to help him save his people, and he finds and mistakenly attacks Barry to harvest the Speedster's power. Of course, the Flash eludes his attempts and discovers his motives, which originally included commandeering Green Lantern's ring. The weird little creature's (assumed to be the next evolutionary stage of man) search wasn't for the hero himself but the weapon, and while he surmises a way to take the Flash's speed, Barry comes up with an alternative plan: traveling back further in time to the point of his super-heroic origin, the Flash gives the alien the chemical-drenched clothes he was wearing when struck by that fateful bolt of lightning, effectively creating a Flash for the future! Unfortunately, this Flash doesn't last long, defeating the monster in the future by grabbing it and accelerating his molecules to the point of mutual spontaneous combustion. See, even in the 98th century, the Flash is hailed as a selfish hero . . . which is what I've been trying to get at in the first place.

As both a character in the continuity of his comic book universe and as an icon of the industry, the Flash has always given of himself to assure victory and success. In the case of his Silver Age transition, the Speedster actually abandoned his original secret identity, becoming the re-imagined Barry Allen, and though Jay Garrick eventually returned as an active member of the Justice Society, Barry has since held the longest stint as the Fastest Man Alive (with Wally West and Impulse carrying the torch afterward). Further, in order to assure that such an epic crossover like Crisis on Infinite Earths boasted relevance and viability, Flash was the hero on the chopping block, willingly, even. Heck, the Flash live action series, though short-lived, set the stage for DC's contemporary tradition of bringing its heroes to the small screen. Superman may have been the first superhero, but the Flash has held the title of being the first to make some ultimate sacrifices.

I don't have to talk about how incredible Carmine Infantino's art is in this issue, do I? Definitive for the character and the era. Perfect superhero dynamics, perhaps DC's answer to the Romitas at Marvel. 'Nuff said.

Perhaps DC is taking the slow and steady method to producing its live action feature films. Yet, when it comes to producing heroes, those who put others before themselves . . . they've always been able to do that in a flash.

Tuesday, June 26, 2007

Robinson Crusoe #1

Robinson Crusoe #1, November 1963-January 1964, Dell Publishing

Something about the teasers for Live Free and Die Hard has inspired me to catch its midnight premiere later tonight, an outing I’ve heretofore exclusively reserved for comic book movies only. I don’t remember the previous three films as vividly as I would, say, the Lethal Weapon franchise, but Bruce Willis’ triumphant return as John McClain, like Harrison Ford’s donning the Indiana Jones mantle again, is downright inspiring. Truly, McClain is the Robinson Crusoe of our generation . . . and until today, I had no idea who Robinson Crusoe was.

Oh, I knew Robinson Crusoe was a famous literary figure, a shipwrecked victim of circumstance that inspired various similar stories, probably including Gilligan’s Island and Tom Hanks’ Castaway. I didn’t know Crusoe’s adventure was credited as the first penned in English, formatted as a legal document to add a layer of realism to the account. Unfortunately, those accomplishments are lost in this Dell comic book adaptation, but considering that I, and undoubtedly countless youth that first read this issue 1963, didn’t know the whole story in the first place, this issue definitely accomplished its mission. Who says comics can’t be educational, too?

In fact, I didn’t just learn about the plight of Robinson Crusoe, but I learned from it, and if I’m ever stranded on a deserted island (if any still exist), I’ll definitely take a page from his playbook to survive. See, based on this comic, Crusoe’s first move was to salvage what supplies he could find on the wrecked ship, then find shelter in a cave, around which he built a literal picket fence to protect his abode from predators. Living off of wild goats’ milk and tortoises for a time, Crusoe eventually learns that he isn’t alone on the island, and he saves a native from a band of cannibals, inadvertently earning a companion he dubs Friday. Held at bay on the island by the cannibals’ village on the neighboring mainland, Crusoe and Friday nearly rescue a passing ship’s crew until they suffer the same fate as Robinson’s vessel – so when another arrives, our heroes are hesitant to help, but when that crew conquers its pirating betrayers, Crusoe and Friday have a one way ticket home.

And how long was Crusoe on that island? Try twenty-eight years, two months, and nineteen days! He puts it best as he leaves his island prison: “After all these years, I feel as if I’m leaving home rather than returning home!” Take that, Tom Hanks! Four years later, you cracked up and starting talking to a volleyball!

Assuming this adaptation is somewhat abbreviated from Daniel Defoe’s original novel, the anonymous contributors to this issue kept a suspenseful pace throughout this version, and the artist’s sketchy ink style, not unlike Rick Leonardi’s, avoided a sloppiness by favoring fluidity, epitomizing the rugged nature of our protagonist’s struggle. For a comic book from the early ‘60s, when artists seemed to prefer solid visuals (and in fact were often the primary storytellers, with the writers layering some semblance of script on afterward), this style strikes me as a bit of a gamble, especially with such reverent source material, but the effort is successful. I certainly didn’t feel stranded in a barren comic book; this issue offers plenty of entertainment.

Interestingly, indicated as a number one, Robinson Crusoe seems to tell the entire tale, so unless our hero gets stranded again, like some strange Lost season finale twist, I don’t see this continuing as a series. Just well, though. There are plenty of other classic works of literature I wouldn’t read otherwise if not as a comic book.

On Sunday night, I briefly examined the concept of television series adaptations, but during the past year, I haven’t had a chance to study the phenomenon from other media. I would imagine that, despite the stereotypical verbose vernacular, classical literature makes for the best comic book adaptation, since, as one of the primary forms of entertainment in its time, prior to broadcast media, its content had to stimulate its audience, asserting mental imagery that makes for perfect inspiration for sequential art. Were the forefathers of literature writing comics two hundred years before the medium was invented? Perhaps no form of art is really an island . . .

Something about the teasers for Live Free and Die Hard has inspired me to catch its midnight premiere later tonight, an outing I’ve heretofore exclusively reserved for comic book movies only. I don’t remember the previous three films as vividly as I would, say, the Lethal Weapon franchise, but Bruce Willis’ triumphant return as John McClain, like Harrison Ford’s donning the Indiana Jones mantle again, is downright inspiring. Truly, McClain is the Robinson Crusoe of our generation . . . and until today, I had no idea who Robinson Crusoe was.

Oh, I knew Robinson Crusoe was a famous literary figure, a shipwrecked victim of circumstance that inspired various similar stories, probably including Gilligan’s Island and Tom Hanks’ Castaway. I didn’t know Crusoe’s adventure was credited as the first penned in English, formatted as a legal document to add a layer of realism to the account. Unfortunately, those accomplishments are lost in this Dell comic book adaptation, but considering that I, and undoubtedly countless youth that first read this issue 1963, didn’t know the whole story in the first place, this issue definitely accomplished its mission. Who says comics can’t be educational, too?

In fact, I didn’t just learn about the plight of Robinson Crusoe, but I learned from it, and if I’m ever stranded on a deserted island (if any still exist), I’ll definitely take a page from his playbook to survive. See, based on this comic, Crusoe’s first move was to salvage what supplies he could find on the wrecked ship, then find shelter in a cave, around which he built a literal picket fence to protect his abode from predators. Living off of wild goats’ milk and tortoises for a time, Crusoe eventually learns that he isn’t alone on the island, and he saves a native from a band of cannibals, inadvertently earning a companion he dubs Friday. Held at bay on the island by the cannibals’ village on the neighboring mainland, Crusoe and Friday nearly rescue a passing ship’s crew until they suffer the same fate as Robinson’s vessel – so when another arrives, our heroes are hesitant to help, but when that crew conquers its pirating betrayers, Crusoe and Friday have a one way ticket home.

And how long was Crusoe on that island? Try twenty-eight years, two months, and nineteen days! He puts it best as he leaves his island prison: “After all these years, I feel as if I’m leaving home rather than returning home!” Take that, Tom Hanks! Four years later, you cracked up and starting talking to a volleyball!

Assuming this adaptation is somewhat abbreviated from Daniel Defoe’s original novel, the anonymous contributors to this issue kept a suspenseful pace throughout this version, and the artist’s sketchy ink style, not unlike Rick Leonardi’s, avoided a sloppiness by favoring fluidity, epitomizing the rugged nature of our protagonist’s struggle. For a comic book from the early ‘60s, when artists seemed to prefer solid visuals (and in fact were often the primary storytellers, with the writers layering some semblance of script on afterward), this style strikes me as a bit of a gamble, especially with such reverent source material, but the effort is successful. I certainly didn’t feel stranded in a barren comic book; this issue offers plenty of entertainment.

Interestingly, indicated as a number one, Robinson Crusoe seems to tell the entire tale, so unless our hero gets stranded again, like some strange Lost season finale twist, I don’t see this continuing as a series. Just well, though. There are plenty of other classic works of literature I wouldn’t read otherwise if not as a comic book.

On Sunday night, I briefly examined the concept of television series adaptations, but during the past year, I haven’t had a chance to study the phenomenon from other media. I would imagine that, despite the stereotypical verbose vernacular, classical literature makes for the best comic book adaptation, since, as one of the primary forms of entertainment in its time, prior to broadcast media, its content had to stimulate its audience, asserting mental imagery that makes for perfect inspiration for sequential art. Were the forefathers of literature writing comics two hundred years before the medium was invented? Perhaps no form of art is really an island . . .

Monday, June 25, 2007

Creatures on the Loose #30

Creatures on the Loose #30, July 1974, Marvel Comics

writer: Doug Moench

artist: George Tuska

inker: Vinnie Colletta

letterer: John Costanza

colorist: L. Lessman

editor: Roy Thomas

As the A Comic A Day challenge comes to its inevitable close this week, Creatures on the Loose #30 is the last Marvel comic I'll be reviewing and thus will be evaluated as such. You see, when Timely Comics became the legendary House of Ideas under the incomparable creativity of Stan Lee and his onslaught of superhero titles, Marvel developed a definitive identity as a comic book publisher that even its long-standing rival DC Comics hadn't yet achieved. Rather than waste his supplemental pages on short stories or crudely illustrated back-up features, as other publishers did, Stan Lee broke the fourth wall and communicated with his audience, founding the Bullpen, Stan's Soapbox, and FOOM, Marvel's official fan club. Lee and company quickly established that the company could be as dynamic an entity as the characters they featured, a phenomenon that affected the industry to this very day.

In fact, one might presume that the Bullpen Bulletins page was comics' first blog, offering a behind the scenes perspective and creative insight to its fans while inadvertently documenting the development of a cultural shifting corporate identity. That's quite an item!

Indeed, Marvel had created a monster, for which they were more commonly known prior to the advent of their superhero canon, and Creatures of the Night is a successful blend of these genres -- indicative of why I chose it as one of the last comics to review this year. This issue stars Man-Wolf, one of Spider-man's rogues, in a solo adventure essentially against himself. See, Man-Wolf is really astronaut John Jameson, Daily Bugle publisher J. Jonah Jameson's son, whose fusion with a celestial pendant transforms him into a werewolf under a full moon. Though readers are treated to a glimpse of this back story, the real action begins when Jameson transforms, tears up his apartment, and lunges into the street, where he coincidentally rescues a helpless couple from a pair of muggers before ex-CIA agent, now special agent Stroud catches up to take the monster down. Stroud pursues Man-Wolf to the Statue of Liberty, where, after a climatic tussle, the beast falls into the ocean. The next issue blurb not only teases that Man-Wolf survived but that this is just the beginning of his tale . . . pun intended!

This issue is classic Marvel, from the trademark simplicity of a protagonist battling his own demons to the dramatic angling of artist George Tuska's page layouts. Tuska blends the Kirby and Romita styles expertly to capture that mighty Marvel manner, which some could criticize nowadays without the knowledge that such similar illustrative efforts were strategic in establishing the company's visual identity. This isn't "the swipe," but the standard of its day. Further, by focusing on supporting characters from Spider-man's ongoing series, fans gain a grander appreciation for all corners of the then-expanding Marvel Universe, nudging that sense of superhero wonder while reinforcing their roots in horror and monster yarns. Yes, Marvel was the Universal Studios of the comic book set, and though its consonant-centric lumbering behemoths aren't as memorable as Frankenstein or the Mummy, fresh takes on the werewolf motif kept Marvel's younger audience interested. Even in today's market where less isn't more anymore, and more still just don't seem like enough, how many villains, especially B-listers like Man-Wolf, get their own series, albeit a serial? Even the Joker's book, which circulated within a few years of Creatures, didn't fare as well in the long run. In this case, the emphasis is less on the characters' status and more in the strength of the story -- which is incidentally, I dare say, a thriller.

Arguably, very little happens in this issue, and like many issues from this era, the captioning is a little much, particularly since the imagery speaks for itself (panel description: Man-Wolf tears up stuff, next: repeat), but I had a similar reaction to Image's Free Comic Book Day offering The Astounding Wolf-Man. It's all foundation work with a bigger scheme, so that writers in future issues can, ahem, shoot for the moon.

Personally, I didn't know much about the Man-Wolf until this issue, fleshing out the origin points of which I was already aware. In fact, the last time I encountered the Man-Wolf was a little over a year ago when I purchased the Spider-man Legends Man-Wolf action figure, a hesitant buy since I'm oblivious to the character, yet I'm a sucker for attempting to collect and display my favorite heroes' rogues. (The toy aisles are packed with Batman and Spider-man variants; it's those bad guys that are so elusive, much like their comic book counterparts!) However, before that, the world met John Jameson (sans pendant) in Spider-man 2, in which he was abandoned by Mary Jane at the altar. Incidentally, I presumed that the third film would tie up that thread by spotlighting a John more determined in the astronaut field than ever, rocketing to the moon and inadvertently bringing back the alien symbiote, which is how the '90s Spider-man animated series introduced Venom, I think. Resolving the one conflict would have transitioned effectively into the other, implying an even stronger sense of continuity between the films and maybe even a cinematic Man-Wolf debut. Perhaps that project is yet to come -- Spider-man 4: Rise of the Man-Wolf! Call me, Sony!

Honestly, it doesn't matter who our heroes fight, because Marvel has assured us that reading the adventure will be fun regardless of the conflict. Heck, they'll even transform some B-list baddie into a bonafide bridge between superhero and creature comics, instilling him with a sense of mystery and sympathy that wouldn't have resulted from some annual appearance as a rogue elsewhere. Stan Lee and his band of merry Marvelites were the real creatures on the loose back in those days, producing comics of a creative quality that still rivals today's new release shelves! In fact, even without the inclusion of Man-Wolf, the Marvel Universe is so rich, its corporate identity so strong, that John Jameson made his way onto the screen anyway. I mean, he's a supporting character to a supporting character, for crying out loud! Thirty-three years after Creatures on the Loose #30, the Man-Wolf, and the company that spawned him, still have their claws.

writer: Doug Moench

artist: George Tuska

inker: Vinnie Colletta

letterer: John Costanza

colorist: L. Lessman

editor: Roy Thomas

As the A Comic A Day challenge comes to its inevitable close this week, Creatures on the Loose #30 is the last Marvel comic I'll be reviewing and thus will be evaluated as such. You see, when Timely Comics became the legendary House of Ideas under the incomparable creativity of Stan Lee and his onslaught of superhero titles, Marvel developed a definitive identity as a comic book publisher that even its long-standing rival DC Comics hadn't yet achieved. Rather than waste his supplemental pages on short stories or crudely illustrated back-up features, as other publishers did, Stan Lee broke the fourth wall and communicated with his audience, founding the Bullpen, Stan's Soapbox, and FOOM, Marvel's official fan club. Lee and company quickly established that the company could be as dynamic an entity as the characters they featured, a phenomenon that affected the industry to this very day.

In fact, one might presume that the Bullpen Bulletins page was comics' first blog, offering a behind the scenes perspective and creative insight to its fans while inadvertently documenting the development of a cultural shifting corporate identity. That's quite an item!

Indeed, Marvel had created a monster, for which they were more commonly known prior to the advent of their superhero canon, and Creatures of the Night is a successful blend of these genres -- indicative of why I chose it as one of the last comics to review this year. This issue stars Man-Wolf, one of Spider-man's rogues, in a solo adventure essentially against himself. See, Man-Wolf is really astronaut John Jameson, Daily Bugle publisher J. Jonah Jameson's son, whose fusion with a celestial pendant transforms him into a werewolf under a full moon. Though readers are treated to a glimpse of this back story, the real action begins when Jameson transforms, tears up his apartment, and lunges into the street, where he coincidentally rescues a helpless couple from a pair of muggers before ex-CIA agent, now special agent Stroud catches up to take the monster down. Stroud pursues Man-Wolf to the Statue of Liberty, where, after a climatic tussle, the beast falls into the ocean. The next issue blurb not only teases that Man-Wolf survived but that this is just the beginning of his tale . . . pun intended!

This issue is classic Marvel, from the trademark simplicity of a protagonist battling his own demons to the dramatic angling of artist George Tuska's page layouts. Tuska blends the Kirby and Romita styles expertly to capture that mighty Marvel manner, which some could criticize nowadays without the knowledge that such similar illustrative efforts were strategic in establishing the company's visual identity. This isn't "the swipe," but the standard of its day. Further, by focusing on supporting characters from Spider-man's ongoing series, fans gain a grander appreciation for all corners of the then-expanding Marvel Universe, nudging that sense of superhero wonder while reinforcing their roots in horror and monster yarns. Yes, Marvel was the Universal Studios of the comic book set, and though its consonant-centric lumbering behemoths aren't as memorable as Frankenstein or the Mummy, fresh takes on the werewolf motif kept Marvel's younger audience interested. Even in today's market where less isn't more anymore, and more still just don't seem like enough, how many villains, especially B-listers like Man-Wolf, get their own series, albeit a serial? Even the Joker's book, which circulated within a few years of Creatures, didn't fare as well in the long run. In this case, the emphasis is less on the characters' status and more in the strength of the story -- which is incidentally, I dare say, a thriller.

Arguably, very little happens in this issue, and like many issues from this era, the captioning is a little much, particularly since the imagery speaks for itself (panel description: Man-Wolf tears up stuff, next: repeat), but I had a similar reaction to Image's Free Comic Book Day offering The Astounding Wolf-Man. It's all foundation work with a bigger scheme, so that writers in future issues can, ahem, shoot for the moon.

Personally, I didn't know much about the Man-Wolf until this issue, fleshing out the origin points of which I was already aware. In fact, the last time I encountered the Man-Wolf was a little over a year ago when I purchased the Spider-man Legends Man-Wolf action figure, a hesitant buy since I'm oblivious to the character, yet I'm a sucker for attempting to collect and display my favorite heroes' rogues. (The toy aisles are packed with Batman and Spider-man variants; it's those bad guys that are so elusive, much like their comic book counterparts!) However, before that, the world met John Jameson (sans pendant) in Spider-man 2, in which he was abandoned by Mary Jane at the altar. Incidentally, I presumed that the third film would tie up that thread by spotlighting a John more determined in the astronaut field than ever, rocketing to the moon and inadvertently bringing back the alien symbiote, which is how the '90s Spider-man animated series introduced Venom, I think. Resolving the one conflict would have transitioned effectively into the other, implying an even stronger sense of continuity between the films and maybe even a cinematic Man-Wolf debut. Perhaps that project is yet to come -- Spider-man 4: Rise of the Man-Wolf! Call me, Sony!

Honestly, it doesn't matter who our heroes fight, because Marvel has assured us that reading the adventure will be fun regardless of the conflict. Heck, they'll even transform some B-list baddie into a bonafide bridge between superhero and creature comics, instilling him with a sense of mystery and sympathy that wouldn't have resulted from some annual appearance as a rogue elsewhere. Stan Lee and his band of merry Marvelites were the real creatures on the loose back in those days, producing comics of a creative quality that still rivals today's new release shelves! In fact, even without the inclusion of Man-Wolf, the Marvel Universe is so rich, its corporate identity so strong, that John Jameson made his way onto the screen anyway. I mean, he's a supporting character to a supporting character, for crying out loud! Thirty-three years after Creatures on the Loose #30, the Man-Wolf, and the company that spawned him, still have their claws.

Sunday, June 24, 2007

Emergency! #1

Emergency! #1, June 1976, Charlton Publications

writer: Joe Gill

artist: Byrne Robotics

editor: Geo. Wildman

If you live in Southern California, or pay attention to news stories with nationwide appeal, you'd understand its residents' wariness toward itself law enforcement and emergency personnel. With headlines about Sheriff Lee Baca allegedly giving celebrity inmate Paris Hilton preferential treatment and about the unfortunate, bloody death of a patient on the floor of the Drew King Medical Center waiting room, one might be hard pressed to remember when police officers, doctors, firefighters, and paramedics were genuine folk heroes worthy of television shows like Emergency! Admittedly, I've never watched an episode of Emergency!, though I imagine it would only run on TV Land anyway, but based on the first issue of its Charlton Comics adaptation, I get the impression that this television series (so, subsequently, its comic book series) honored its law enforcement and first response team protagonists. From the eye-catching watercolor cover by (Joe?) Staton, depicting firefighters harrowingly saving an unconscious victim from a burning building, we the readers instantly understand the dichotomy of their mission; while their faces betray their own fear, they act anyway, which is a true mark of heroism. Who saves even Superman can't feel a little fear flying into fight now and then?

But I digress. First, Emergency! #1 was a compelling comic book, with a dramatic first page splash of an ambulance hitting the street in response to, well, an emergency. Dual plotlines converge when a warehouse fire is traced to a hospital victim with radiation burns; the warehouse's owner is initially suspected because of his abnormal cache of radioactive material, all of the drums are legally registered. So, some attention falls on the mystery burn patient, who ends up eluding a prolonged hospital stay and seemingly has a rap sheet for numerous crimes, including theft and arson. Paramedic John Gage takes the case, which is initially befuddling since plenty of police officers are around to help, but his emphasis on the potential biohazard of his suspect permits some suspension of belief. Really, I would imagine that investigations like this are tangled in red tape, and only in retrospect did I realize that the media and their inherent exploitive skepticism of "the process" were absent supporting characters, but that speaks to the contemporary pop culture standard of celebrity and law enforcement. Much like this review, Emergency #1 hits a wall when Gage learns where his suspect might be hiding, and for several pages he talks about hitting the joint:

"He hangs out with a bunch of punks at Leo's Grill."

"I've got an idea where he might go, Dixie!"

"Unless I miss my guess, Davin will head for his buddies -- and that means Leo's Bar and Grill!"

"I'm sure he's hanging out at a place called Leo's Grill."

"I hope Davin is in Leo's Bar and Grill."

That's four pages' worth of anticipation that builds to a conversation Gage and an officer have with Davin when they finally find him at, yes, Leo's Bar and Grill. While his punk friends offer some resistance that leads to a climatic shoot-out, a moment of poignancy concludes this investigation when the nurse beholds a dying-from-radiation-poisoning Davin and muses, "Why do people wreck their lives like this?" Though she might have been pondering the nature of crime in general, we the readers never really find out why Davin himself was such a fiend for radium chloride . . . his motive is never revealed, and in fact never really called into question! Perhaps it's just that valuable -- apparently it has the ability to poison punks, and potentially good crime stories.

Still, if Emergency! was intended to attract a wider audience to its native TV show, I say mission accomplished. If I catch it on my DirecTV preview guide, I'll definitely select it, if only to see if live action holds up to the intensity of adapted graphic storytelling.

Interestingly, when I first read this issue, I missed the artist credit as "Byrne Robotics." Indeed, this comic features some of John Byrne's earliest work in the industry, and though his signature is initially obscured by his attempts to capture the likenesses of the television series' cast, further examination reveals some traces of his work, even by today's standards. I confirmed these facts on Wikipedia but couldn't find Emergency! on Byrne's own bibliography at Byrne Robotics. Could he be ashamed of this work, even with its blatant support of our nation's law enforcement and EMT officers?

However, the A-Team proved just a few years after Emergency!'s heyday that one need not be on the right side of the law to enforce it. Until I read their Marvel Comics adaptation, I never realized that their hoarsely asserted backstory from the opening credits of their TV show (sans season five, by which time they'd jumped the shark with a techno remix of their signature theme song) was the broadcast equivalent of Marvel's one or two sentence origin synopses at the top of their title pages in the '70s and '80s. No wonder The A-Team makes for such a marvelous read! Credited as the art director, John Romita obviously went to great lengths to make sure that the A-Team was drawn the Marvel way, and though "average Joe" characters like Murdock and Face lose some similarity to their actors' likeness in the transition, definitive characters like Hannibal and B.A. are on point. In fact, in some panels, Hannibal's cocky smirk looks more like something from the pages of a Mad Magazine spoof strip, but I understand that this comic book series parallels the show's first season; Hannibal's character developed a real gravitas in seasons two and three, especially in the episode "Deadly Maneuvers." Again, but I digress.

What Emergency! #1 lacked in the motives department Marvel's The A-Team makes up for in spades. In fact, having read issues #1 and #2, while some of the "mysterious" motivations are too transparent to truly illicit intrigue, others are a bit too far-fetched for my liking. For example, in the first issue, B.A. insists that his old friend has nothing to do with a diamond heist despite evidence to the contrary, and later we learn that his old buddy is in fact an FBI agent working undercover. Seriously, I saw it coming a mile away. Then, in issue #2, when two Asian brothers, co-creators of a multi-million dollar video game company (in 1984?) hire the A-Team to find their kidnapped father of two years, Pops reveals that he kidnapped himself to start a cult bent on ancient Japanese traditions. Oh-kay. That's a plot so mundane I would have saved it for season five.

But, hark, what's this? A potential The A-Team/The Greatest American Hero crossover? When B.A.'s old buddy reveals that he's an FBI agent, he explains that he and his partner Bill Maxwell have been on the case for awhile. Die hard fans (like me) will recognize Maxwell's name as the "spook" that discovered the alien super suit with Ralph Hinkley in the '80s series The Greatest American Hero! We never actually see Bill, but the reference isn't that surprising considering both TV shows were products of Stephen J. Cannell Productions. Was Marvel hinting at a possible Cannell-verse? Unfortunately, fans never saw such a crossover really come to fruition. I guess that's what fan fiction is for.

Unlike Emergency #1, which caught my eye because of the Charlton bull's eye and that Staton cover, I can't imagine folks that didn't watch The A-Team were suddenly inspired to do so because of the Marvel comic book, which, based on its cover imagery, was just another Mr. T vehicle in the early '80s anyway. Seriously, a Saturday morning cartoon and a cereal weren't enough for the Baracan one? Actually, by issue #2, the interior story featured more of the others' trademarked personalities, which was a relief for comprehensive fans like me . . . and I did develop a greater understanding of what comic book adaptations need to tick. Fortunately, both of these series had that critical ingredient: character. Though a bit bland and repetitive at times, Gage is a heroic figure, determined in his quest while realizing the big picture, as well. If only the character of contemporary law enforcement would be so highly regarded. Nowadays, the television emphasis is more on the legal process, thanks to successes like Law & Order and Boston Legal. When it comes to cops, perhaps because of those controversial headlines, they reserve the right to remain silent. Who can blame 'em?

writer: Joe Gill

artist: Byrne Robotics

editor: Geo. Wildman

If you live in Southern California, or pay attention to news stories with nationwide appeal, you'd understand its residents' wariness toward itself law enforcement and emergency personnel. With headlines about Sheriff Lee Baca allegedly giving celebrity inmate Paris Hilton preferential treatment and about the unfortunate, bloody death of a patient on the floor of the Drew King Medical Center waiting room, one might be hard pressed to remember when police officers, doctors, firefighters, and paramedics were genuine folk heroes worthy of television shows like Emergency! Admittedly, I've never watched an episode of Emergency!, though I imagine it would only run on TV Land anyway, but based on the first issue of its Charlton Comics adaptation, I get the impression that this television series (so, subsequently, its comic book series) honored its law enforcement and first response team protagonists. From the eye-catching watercolor cover by (Joe?) Staton, depicting firefighters harrowingly saving an unconscious victim from a burning building, we the readers instantly understand the dichotomy of their mission; while their faces betray their own fear, they act anyway, which is a true mark of heroism. Who saves even Superman can't feel a little fear flying into fight now and then?

Fortunately, since this is the first of my seven last reviews of my consecutive year-long A Comic A Day personal challenge, and thus a strategic choice, this issue offers two opportunities for analysis: one, as the aforementioned adaptation of a TV series, albeit one I haven't seen, so two, a comparison piece for an comic adaptation of a show I love, The A-Team. Yes, Mr. T has made a few appearances here already (and earned a mention as one of my "man-crushes" in my recent LiveJournal posts), but only recently did I acquire three of Marvel's The A-Team books -- cheaply, I might add. While '80s nostalgia is in full swing with both TMNT and Transformers in theaters this year, some back issues will forever be relegated to the twenty-five cent bin. Honestly, just finding those comics, on the heels of acquiring all five seasons of the original TV show on DVD no less, was priceless.

But I digress. First, Emergency! #1 was a compelling comic book, with a dramatic first page splash of an ambulance hitting the street in response to, well, an emergency. Dual plotlines converge when a warehouse fire is traced to a hospital victim with radiation burns; the warehouse's owner is initially suspected because of his abnormal cache of radioactive material, all of the drums are legally registered. So, some attention falls on the mystery burn patient, who ends up eluding a prolonged hospital stay and seemingly has a rap sheet for numerous crimes, including theft and arson. Paramedic John Gage takes the case, which is initially befuddling since plenty of police officers are around to help, but his emphasis on the potential biohazard of his suspect permits some suspension of belief. Really, I would imagine that investigations like this are tangled in red tape, and only in retrospect did I realize that the media and their inherent exploitive skepticism of "the process" were absent supporting characters, but that speaks to the contemporary pop culture standard of celebrity and law enforcement. Much like this review, Emergency #1 hits a wall when Gage learns where his suspect might be hiding, and for several pages he talks about hitting the joint:

"He hangs out with a bunch of punks at Leo's Grill."

"I've got an idea where he might go, Dixie!"

"Unless I miss my guess, Davin will head for his buddies -- and that means Leo's Bar and Grill!"

"I'm sure he's hanging out at a place called Leo's Grill."

"I hope Davin is in Leo's Bar and Grill."

That's four pages' worth of anticipation that builds to a conversation Gage and an officer have with Davin when they finally find him at, yes, Leo's Bar and Grill. While his punk friends offer some resistance that leads to a climatic shoot-out, a moment of poignancy concludes this investigation when the nurse beholds a dying-from-radiation-poisoning Davin and muses, "Why do people wreck their lives like this?" Though she might have been pondering the nature of crime in general, we the readers never really find out why Davin himself was such a fiend for radium chloride . . . his motive is never revealed, and in fact never really called into question! Perhaps it's just that valuable -- apparently it has the ability to poison punks, and potentially good crime stories.