writer: Cary Bates

penciller: Carmine Infantino

inker: Dennis Jensen

colorist: Gene D'Angelo

letterer: Milt Snapinn

editor: Mike W. Barr

While Marvel's superheroes have attained iconic status in worldwide pop culture and continue to star in their own feature length films, DC's roll call are the founding fathers of the genre, a feat that needs no supplemental media to prove its significance. However, while fans have criticized DC's (and, really, Warner Brothers') inability to produce comics-to-film projects as quickly as Marvel (sixteen films from the House of Ideas pales to DC's three in the last decade . . . and I'm including Catwoman), the Distinguished Competition has conversely cornered the television market, producing the undeniably successful Smallville and a multitude of animated series and straight-to-DVD animated specials. In fact, considering these shows, the WB may be responsible for more total hours of filmed entertainment than Marvel since the comparison became viable in the late '90s (inspired not by Spider-man, but Blade). So, all that is to say, I'm standing by the DC stable. I may not agree with the current direction of the DC Universe, but I have plenty of nostalgic canon at my disposal.

Which is why I was so excited to read Flash #309, which is actually a timely review considering last week's tumultuous events in the Scarlet Speedster's life. Since I'm not collecting The Flash and have been blissfully ignorant of most of the 52-related phenomenon, I'll confess I'm not completely privy to that latest issue's details, but a flip of the book gave me a fair impression of its implications. Again, I may not agree with this direction, but it proves the point the issue of The Flash that I read today solidified: of all of DC's canon, the Flash is the most influential to the superhero genre. Now, I know what my fellow fanboys might be thinking -- when compared to Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, and even Captain Marvel, why would the Flash hold the distinction of "most influential?" I mean, he really just runs, right? Yes, he does, which is my point exactly. The Flash has always been a progressive, as a concept and as a character.

First of all, in his original Golden Age incarnation, the Flash was a gamble, because his sole power was but one of Superman's -- a concept not as well defined in the hit-or-miss superhero cavalcade of the '40s, but true nevertheless. Further, the Flash's reboot, the first official revamp in superhero fiction, initiated the Silver Age and redefined the way comics told stories. Despite their many interpretations through the '80s, superheroes remained colorful campy adventurers until DC's first Crisis, you know, the one on Infinite Earths, in which the company actually sacrificed one of their own to again usher a new generation of characters into their ranks. Indeed, before Robin and Superman died or Batman suffered a broken back, Barry Allen willingly bit the big one, becoming the first widely known superhero to die. None of the other similar gimmicks inflicted to DC's other heroes have lasted as long. The Flash has always been racing ahead of his time.

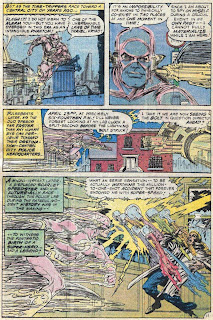

Which brings me to The Flash #309, a refreshingly villain-free story that epitomizes why the Flash is the most innovative superhero of all. In this issue, a refugee from a warring future travels back in time in search of a legendary Justice Leaguer to help him save his people, and he finds and mistakenly attacks Barry to harvest the Speedster's power. Of course, the Flash eludes his attempts and discovers his motives, which originally included commandeering Green Lantern's ring. The weird little creature's (assumed to be the next evolutionary stage of man) search wasn't for the hero himself but the weapon, and while he surmises a way to take the Flash's speed, Barry comes up with an alternative plan: traveling back further in time to the point of his super-heroic origin, the Flash gives the alien the chemical-drenched clothes he was wearing when struck by that fateful bolt of lightning, effectively creating a Flash for the future! Unfortunately, this Flash doesn't last long, defeating the monster in the future by grabbing it and accelerating his molecules to the point of mutual spontaneous combustion. See, even in the 98th century, the Flash is hailed as a selfish hero . . . which is what I've been trying to get at in the first place.

As both a character in the continuity of his comic book universe and as an icon of the industry, the Flash has always given of himself to assure victory and success. In the case of his Silver Age transition, the Speedster actually abandoned his original secret identity, becoming the re-imagined Barry Allen, and though Jay Garrick eventually returned as an active member of the Justice Society, Barry has since held the longest stint as the Fastest Man Alive (with Wally West and Impulse carrying the torch afterward). Further, in order to assure that such an epic crossover like Crisis on Infinite Earths boasted relevance and viability, Flash was the hero on the chopping block, willingly, even. Heck, the Flash live action series, though short-lived, set the stage for DC's contemporary tradition of bringing its heroes to the small screen. Superman may have been the first superhero, but the Flash has held the title of being the first to make some ultimate sacrifices.

I don't have to talk about how incredible Carmine Infantino's art is in this issue, do I? Definitive for the character and the era. Perfect superhero dynamics, perhaps DC's answer to the Romitas at Marvel. 'Nuff said.

Perhaps DC is taking the slow and steady method to producing its live action feature films. Yet, when it comes to producing heroes, those who put others before themselves . . . they've always been able to do that in a flash.

No comments:

Post a Comment